|

Between the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, the US federal government has committed to investing billions of dollars to decarbonize cities and towns across the country, including funding for urban parks and forests, home energy efficiency, pollution mitigation, and more.

A recent report by Indiana University researchers, however, finds that around 4 out of 5 Hoosier cities and towns lack the resources to apply for sustainability-focused federal grant funding and would need additional staff to manage funds if they received it. The findings come as the Biden administration rolls out new details on how local governments can apply for funding. Keep reading here.

0 Comments

How does a local government's existing capabilities relate to its sustainability commitments?8/8/2020 Public managers serve many sovereigns, work within fiscal constraints, and face competing demands for finite resources. Our latest work in Public Administration Review applies a strategic management lens to local government sustainability capabilities to examine the conditions under which local governments diversify into new areas of service delivery and when they do not. Building on recent efforts to apply resource‐based theories to the public sector, we distinguish between more and less fungible capabilities and posit that local government officials make such commitments to enhance the competitiveness of their communities. Two surveys of U.S. cities provide evidence that governments that rely on tax incentive‐based development approaches may struggle to make sustainable development gains. Such cities are more likely to devote resources disproportionately to delivering benefits to firms at the risk of incurring increasing opportunity costs over time. Prior commitments to traditional, firm‐based economic development capabilities appear to inhibit their ability to pursue broader sustainability policies. However, economic development strategic planning can also positively influence some investments in greenhouse gas reduction efforts. Moreover, cities facing more competition for development are more likely to integrate planning and performance measurement to assess their sustainability commitments.

The key takeaways for sustainability practice: - Local governments can make sustainability gains by identifying fungible organizational capabilities that can be more easily reassigned to similar functions. - Strategic planning that involves both economic development and sustainability efforts can identify more avenues for leveraging existing capabilities. - Cities located in more competitive markets for economic development should devote greater attention to performance measurement and management to justify investing resources in sustainable development efforts. - Over-reliance on tax-incentive-based economic development strategies, which often drain communities of resources, can impair broader commitments to sustainable development. SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease (COVID-19), has exposed weaknesses—not in the United States’ federalist fabric, but in its degraded administrative systems and capacities. This article in the American Review of Public Administration argues that individual citizens—as tribalized and fractious as they seem—have been poorly served by public officials with career incentives to avoid risks, downplay long-term threats, and enact administrative burdens. Public administrators must advance a more equity-based assessment of vulnerabilities in American communities and more risk-based communication strategies. Citizens have never had access to more information—and thus more difficulty in discerning facts from fallacy. Public administrators are the planners, engineers, analysts, auditors, lawyers, and managers on the front lines of this and future existential crises. It is their job to sift through the information environment and—however boundedly—tackle problems. For the sake of the American democracy, public administrators need to regain the people’s trust. They could start by leveling with them about the challenges ahead.

Read on here. House Democrats in June unveiled a 547-page climate action plan which includes a proposed re-start of the U.S. Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant (EECBG) Program. While the plan is a political document unlikely to become law this year, the EECBG portion is good public policy. Let me explain why.

The EECBG program was funded as part of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). It steered approximately $3.2 billion to 2,187 state, local and tribal governments, which undertook more than 7,400 energy-efficiency projects. Despite documented energy savings and job-creation, the program was never re-funded. Under the House Democrat plan, the EECBG re-start would be "for building electrification, which would expedite full decarbonization of buildings and early adoption of more ambitious building codes to achieve net-zero emissions." Local governments love these kinds of green-building projects, but often struggle financing or incentivizing them. Before local governments could get EECBG funds, they would need to "identify the communities most in need of energy efficiency improvements, including low-income communities with high energy cost burdens, and distribute funds according to those needs." This is basically what Megan Hatch, Eric Stokan and I recommend in a recent Public Administration Review article focused on equity-based responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. While the program was deemed a failure by some within the Department of Energy (largely because of implementation delays ), it produced a net job gain of 62,902 job years, avoided 25.7 million metric tons of carbon emissions, and led to $5.2 billion in total cumulative savings on energy bills, of which 70% came from residential consumers. It also helped many local governments which lacked the financial and technical capacity to launch their own programs from scratch. While hundreds of U.S. local governments have started sustainability efforts over the last two decades, the vast majority of these efforts minimize or ignore social equity. Research we published in Urban Affairs Review suggests local governments are also heavily path-dependent - especially when it comes to efforts to address racial and social inequities. We think re-starting and modifying the EECBG program to target social vulnerabilities is good policy because of the empirical evidence of the program's implementation lessons – but also because of the loss aversion tendencies of local governments. In essence, local governments are risk-averse when it comes to innovative policy endeavors. But they are more likely to double-down on their past investments. This is the difference between exploration strategies and exploitation strategies. When it comes to community development, climate policy and social equity, local governments are far more likely to exploit (stick with) what they already know how to do. In a recent study published in the Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, William Swann, Richard Feiock and I examined this risk-aversion tendency in the context of the EECBG program. Using surveys of EECBG program participants, our study found that local governments engaged in risk-seeking behavior in order to minimize the potential loss of their prior effort. In other words, they were more risk-taking and likely to continue their sustainability efforts despite bad experiences, because they already had sunk costs or "skin in the game." However, our experimental results confirmed that local government administrators are risk-averse when asked to evaluate the merits of initiating a new sustainability program. The bottom line: federal instigation of sustainability programs is likely to be a more effective catalyst of climate action and social justice than simply leaving local governments alone. Using block grant-style programs to achieve policy aims also has the virtue of being a tried-and-true mechanism local governments have a lot of experience using. Like it or not, our federalist system has created tremendous local government dependencies on federal grants and policy directives. Re-starting a program like EECBG has the potential to provide both. Social Inequities must be a Focus of the Post-COVID Recovery Planning for Local Governments6/30/2020 COVID‐19 is exposing a nexus between communities disproportionately suffering from underlying health conditions, policy‐reinforced disparities, and susceptibility to the disease. As the virus spreads, policy responses will need to shift from focusing on surveillance and mitigation to recovery and prevention. Local governments, with their histories of mutual aid and familiarity with local communities, are capable of meeting these challenges. However, funding must flow in a flexible enough fashion for local governments to tailor their efforts to preserve vital services and rebuild local economies. Co-authors Megan Hatch, Eric Stokan and I argue in this Public Administration Review article that the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) and the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant (EECBG) programs are mechanisms for how to provide funds in a manner adaptable to local context while also focusing on increasing social equity. Administrators must emphasize the fourth pillar of public administration ‐‐ social equity ‐‐ in framing government responses to the pandemic.

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes coronavirus disease (COVID-19), has exposed a lack of governmental capacity and preparedness for pandemics within the United States and around the globe since its emergence in December 2019. Besides the much-publicized failures to make enough tests and medical supplies available, U.S. federal, state, and local governmental officials have struggled to coordinate a consistent, coherent message for citizens to social-distance. President Donald Trump has quarreled with governors and belittled the media. Federal health agency experts have been sidelined or contradicted. Some states, such as Florida and Texas, have appeared to prioritize the economic consequences of the pandemic.3 In households across the country, citizens are being exposed daily to contradictory arguments from various messengers on the need to shelter vs. preserve the economy.

I recently conducted an artefactual survey experiment on a nationwide panel of U.S. adults, in which public-health information regarding COVID-19 was transmitted via alternative issue frames and different government messengers. The analysis suggests the use of the pro-health frame generally had a positive effect -- in tandem with a presidential messenger -- on respondents’ preference to avoid unnecessary social activity. Conversely, the use of a pro-economic frame had a negative effect on the preference of respondents for social-distancing. Effective public messaging during emergencies may be shaped by the type of messenger. But clearly, the message matters. As climate change challenges the sustainability of existing water supplies, many cities must transition toward more sustainable water management practices to meet demand. However, scholarly knowledge of the factors that drive such transitions is lacking, in part due to the dearth of comparative analyses in the existing transitions literature.

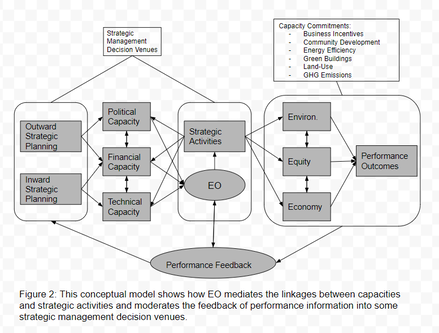

This study is the starting point for a recent $1.5 million National Science Foundation grant my team from Arizona State University, Vanderbilt and the University of Nevada Reno recently received. The study seeks to identify common factors associated with transitions toward sustainability in urban water systems by comparing transitions in three cases: Miami, Las Vegas, and Los Angeles. For each case, we develop a data-driven narrative that integrates case-specific contextual data with standardized, longitudinal metrics of exposures theorized to drive transition. We then compare transitions across cases, focusing on periods of accelerated change (PoACs), to decouple generic factors associated with transition from those unique to individual case contexts. From this, we develop four propositions about transitions toward sustainable urban water management. We find that concurrent exposure to water stress and heightened public attention increases the probability of a PoAC (1), while other factors commonly expected to drive transition (e.g. financial stress) are unrelated (2). Moreover, the timing of exposure alignment (3) and the relationship between exposures and transition (4) may vary according to elements of the system’s unique context, including the institutional and infrastructure design and hydro-climatic setting. These propositions, as well as the methodology used to derive them, provide a new model for future research on how cities respond to climate-driven water challenges. Over the next four years, we will be working to scale up this approach to additional cities.  Local government managers are often tasked with running a political gauntlet: preserving or enhancing services as resources become more constrained, responding to a myriad of stakeholders with diverse preferences, and proactively considering long-term opportunities and threats. When it comes to complex policy problems like sustainability, this is often described with the 'chicken-and-egg' cliché. Organizations that have resources can afford to be more risk-taking and innovative, while those with fewer resources struggle to make gains. Linking strategic management to performance has been called essential for public managers to confront pernicious environmental and community problems in the twenty-first century. I am especially interested in whether doing so can help struggling local governments overcome their own resource constraints. In a new study, co-author William Swann and I examined the role that a local government's "entrepreneurial orientation" - the willingness to take risks, be proactive and innovate - play in the strategic management of sustainability. What we found was that an organization's "EO" plays a much larger, direct role in the cyclical process of building and using organizational capacities, which are the fiscal, human, and political resources managers cultivate and deploy. However, EO by itself had no direct influence on performance gains. So, what does this mean? We illustrate the significance of the findings as a "strategy-capacity-performance" system in which EO is stoked by the levels of organizational capacities but also acts as a kinetic energizer of sorts. In other words, EO matters - but not because it directly enhances performance. Rather, it facilitates the development of the capacities and strategies which do so. This is practically important for several reasons. The management reform literature of the last three decades seems to equate innovative and "out of the box" thinking in public organizations with the personal characteristics of their leaders. While leadership is undoubtedly important, our work suggests public organizations need more than just charismatic or visionary leaders - they need new processes or routines to inculcate major performance gains. Developing an entrepreneurial culture is important for "sustaining" sustainability, but EO alone is not enough. A second implication is that managers remain keenly risk-averse. Our interviews with city managers in the Chicago region drove this point home. Managers must assess the level of risk-taking which is acceptable within their communities. While this may seem intuitive, it is also problematic because managers -- like all humans - tend to cognitively overweight the potential for losses relative to gains. "We do not take risks. We may say we do, but we don't," one manager reiterated. This is likely only part of the story (managers do take risks when facing potential losses). But it suggests that proponents of sustainability need to think of ways to re-frame the risks and rewards of local sustainability (and researchers need to devote more effort to examining loss aversion and framing effects in this context). A final implication is that establishing strategic management processes or routines can have a broad impact; any local government can do this. It shouldn't be acceptable for local government officials to claim they cannot be innovative or proactive simply because they lack resources. Hopefully, this and future work we have in the pipeline can help managers and policymakers understand that making sustainability gains requires a process for developing capacities, carving out a space for acceptable actions, and learning from experiences. |

AuthorI work as an Assistant Professor at the O'Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University Bloomington. There, I direct the MGMT Lab. Archives

January 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed