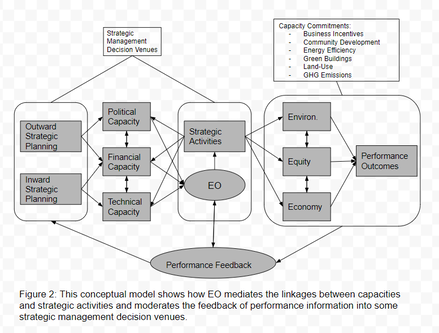

Local government managers are often tasked with running a political gauntlet: preserving or enhancing services as resources become more constrained, responding to a myriad of stakeholders with diverse preferences, and proactively considering long-term opportunities and threats. When it comes to complex policy problems like sustainability, this is often described with the 'chicken-and-egg' cliché. Organizations that have resources can afford to be more risk-taking and innovative, while those with fewer resources struggle to make gains. Linking strategic management to performance has been called essential for public managers to confront pernicious environmental and community problems in the twenty-first century. I am especially interested in whether doing so can help struggling local governments overcome their own resource constraints. In a new study, co-author William Swann and I examined the role that a local government's "entrepreneurial orientation" - the willingness to take risks, be proactive and innovate - play in the strategic management of sustainability. What we found was that an organization's "EO" plays a much larger, direct role in the cyclical process of building and using organizational capacities, which are the fiscal, human, and political resources managers cultivate and deploy. However, EO by itself had no direct influence on performance gains. So, what does this mean? We illustrate the significance of the findings as a "strategy-capacity-performance" system in which EO is stoked by the levels of organizational capacities but also acts as a kinetic energizer of sorts. In other words, EO matters - but not because it directly enhances performance. Rather, it facilitates the development of the capacities and strategies which do so. This is practically important for several reasons. The management reform literature of the last three decades seems to equate innovative and "out of the box" thinking in public organizations with the personal characteristics of their leaders. While leadership is undoubtedly important, our work suggests public organizations need more than just charismatic or visionary leaders - they need new processes or routines to inculcate major performance gains. Developing an entrepreneurial culture is important for "sustaining" sustainability, but EO alone is not enough. A second implication is that managers remain keenly risk-averse. Our interviews with city managers in the Chicago region drove this point home. Managers must assess the level of risk-taking which is acceptable within their communities. While this may seem intuitive, it is also problematic because managers -- like all humans - tend to cognitively overweight the potential for losses relative to gains. "We do not take risks. We may say we do, but we don't," one manager reiterated. This is likely only part of the story (managers do take risks when facing potential losses). But it suggests that proponents of sustainability need to think of ways to re-frame the risks and rewards of local sustainability (and researchers need to devote more effort to examining loss aversion and framing effects in this context). A final implication is that establishing strategic management processes or routines can have a broad impact; any local government can do this. It shouldn't be acceptable for local government officials to claim they cannot be innovative or proactive simply because they lack resources. Hopefully, this and future work we have in the pipeline can help managers and policymakers understand that making sustainability gains requires a process for developing capacities, carving out a space for acceptable actions, and learning from experiences.

0 Comments

Institutions are the rules, norms or conventions which bind collective human activities, structure interactions between people and organizations, and provide the incentives for behavior. This is a typical academic definition of a concept which I have spent years researching and trying to relate to the broader world occupied by non-academics (i.e., public managers, students, media, consumers and producers of government services). Institutions matter. Just ask the FBI. Or, the International City/County Management Association. Or any lawyer. But they are a difficult topic to quantify, model and relate to practice. I used to be a political reporter covering state legislatures and governors. Every day, my editor would bust my chops about making arcane Capitol processes and conflict meaningful for a general audience. I have a similar frustration in academia. So, I guess this is my manifesto to try and do better. Starting this fall, I am re-organizing my research agenda along some lines which have been percolating in my head for several years. I am starting a new job at Indiana University and standing up a research lab organized around the analysis and synthesis of institutional and behavioral change over time. I’m calling the lab the Metropolitan Governance and Management Transitions (MGMT) Lab, and I’m seeding it with some funding from a National Science Foundation grant and a few other sources (hopefully many more in the future). The MGMT Lab will strive to advance our understanding of the drivers and barriers of local government transitions toward more sustainable development and resource management. I know that sounds a bit amorphous. But, there is a lot of nuance and complexity involved in the arena of urban sustainability. There are environmental issues, equity issues and economic issues. Scholars can spend their entire careers at the macro-, meso- or micro-levels of analysis. I want to do work that scales up and down. I am particularly interested in mid-sized and smallish communities which don’t have the resources of a Chicago or New York to hire chief data officers, create sustainability offices, or develop their own mini-Paris Accord climate-action plans. There are many wonderful academic research labs on universities devoted to advancing our theoretical understanding of local governance and sustainability. Rather than organizing this lab around a particular theoretical framework, it will be focused on advancing understanding of how communities a) formulate long-term sustainability strategies; b) develop the capacities to carry them out; and c) assess and improve performance. Think of it as a social science research station, in which the dynamism and experiences of local governments are studied over time. The actual research will involve a combination of sequential and embedded mixed-methods research designs that include collecting text-based data on local planning efforts, survey and interview data on management capacities and routines, case studies to strengthen causal inference, and survey experiments to test behavioral applications. Academic research has a lot to offer communities which fall along the entire spectrum of sustainability: those attempting to formulate long-term sustainability and resiliency strategies; those attempting to develop resources for implementation; and those attempting to track their progress and make adjustments. But to do so, I need to build collaborative partnerships and engage as many stakeholders as possible. For instance, two IU-based centers have agreed to be collaborative partners to this future work (once it’s funded): the IU Center for Rural Engagement, which collaborates with Indiana communities on pressing challenges; and the IU Environmental Resilience Institute, which develops forecasts, strategies and communication methods to enhance environmental resilience. Over time, the MGMT Lab will build infrastructure for future research by developing a comprehensive database of variables generated across the three phases. This dataset will facilitate predictive modeling and will be scalable for other states. Students will train in both qualitative and quantitative analysis. Research efforts and findings will be incorporated as learning modules into local government management classes. Down the road, community workshops, outreach and webinars will be in the works. I’m excited about the potential for this work, but I am also cognizant that this is a learning process. Hopefully, the fruits will be concrete policy prescriptions which can help struggling communities adapt and thrive in a rapidly changing world. In the meantime, feel free to reach out with any recommendations, concerns, opportunities: [email protected] |

AuthorI work as an Assistant Professor at the O'Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University Bloomington. There, I direct the MGMT Lab. Archives

January 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed