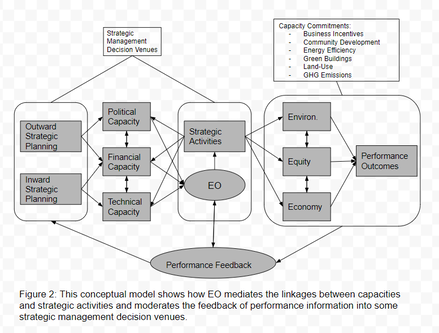

Local government managers are often tasked with running a political gauntlet: preserving or enhancing services as resources become more constrained, responding to a myriad of stakeholders with diverse preferences, and proactively considering long-term opportunities and threats. When it comes to complex policy problems like sustainability, this is often described with the 'chicken-and-egg' cliché. Organizations that have resources can afford to be more risk-taking and innovative, while those with fewer resources struggle to make gains. Linking strategic management to performance has been called essential for public managers to confront pernicious environmental and community problems in the twenty-first century. I am especially interested in whether doing so can help struggling local governments overcome their own resource constraints. In a new study, co-author William Swann and I examined the role that a local government's "entrepreneurial orientation" - the willingness to take risks, be proactive and innovate - play in the strategic management of sustainability. What we found was that an organization's "EO" plays a much larger, direct role in the cyclical process of building and using organizational capacities, which are the fiscal, human, and political resources managers cultivate and deploy. However, EO by itself had no direct influence on performance gains. So, what does this mean? We illustrate the significance of the findings as a "strategy-capacity-performance" system in which EO is stoked by the levels of organizational capacities but also acts as a kinetic energizer of sorts. In other words, EO matters - but not because it directly enhances performance. Rather, it facilitates the development of the capacities and strategies which do so. This is practically important for several reasons. The management reform literature of the last three decades seems to equate innovative and "out of the box" thinking in public organizations with the personal characteristics of their leaders. While leadership is undoubtedly important, our work suggests public organizations need more than just charismatic or visionary leaders - they need new processes or routines to inculcate major performance gains. Developing an entrepreneurial culture is important for "sustaining" sustainability, but EO alone is not enough. A second implication is that managers remain keenly risk-averse. Our interviews with city managers in the Chicago region drove this point home. Managers must assess the level of risk-taking which is acceptable within their communities. While this may seem intuitive, it is also problematic because managers -- like all humans - tend to cognitively overweight the potential for losses relative to gains. "We do not take risks. We may say we do, but we don't," one manager reiterated. This is likely only part of the story (managers do take risks when facing potential losses). But it suggests that proponents of sustainability need to think of ways to re-frame the risks and rewards of local sustainability (and researchers need to devote more effort to examining loss aversion and framing effects in this context). A final implication is that establishing strategic management processes or routines can have a broad impact; any local government can do this. It shouldn't be acceptable for local government officials to claim they cannot be innovative or proactive simply because they lack resources. Hopefully, this and future work we have in the pipeline can help managers and policymakers understand that making sustainability gains requires a process for developing capacities, carving out a space for acceptable actions, and learning from experiences.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI work as an Assistant Professor at the O'Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University Bloomington. There, I direct the MGMT Lab. Archives

January 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed